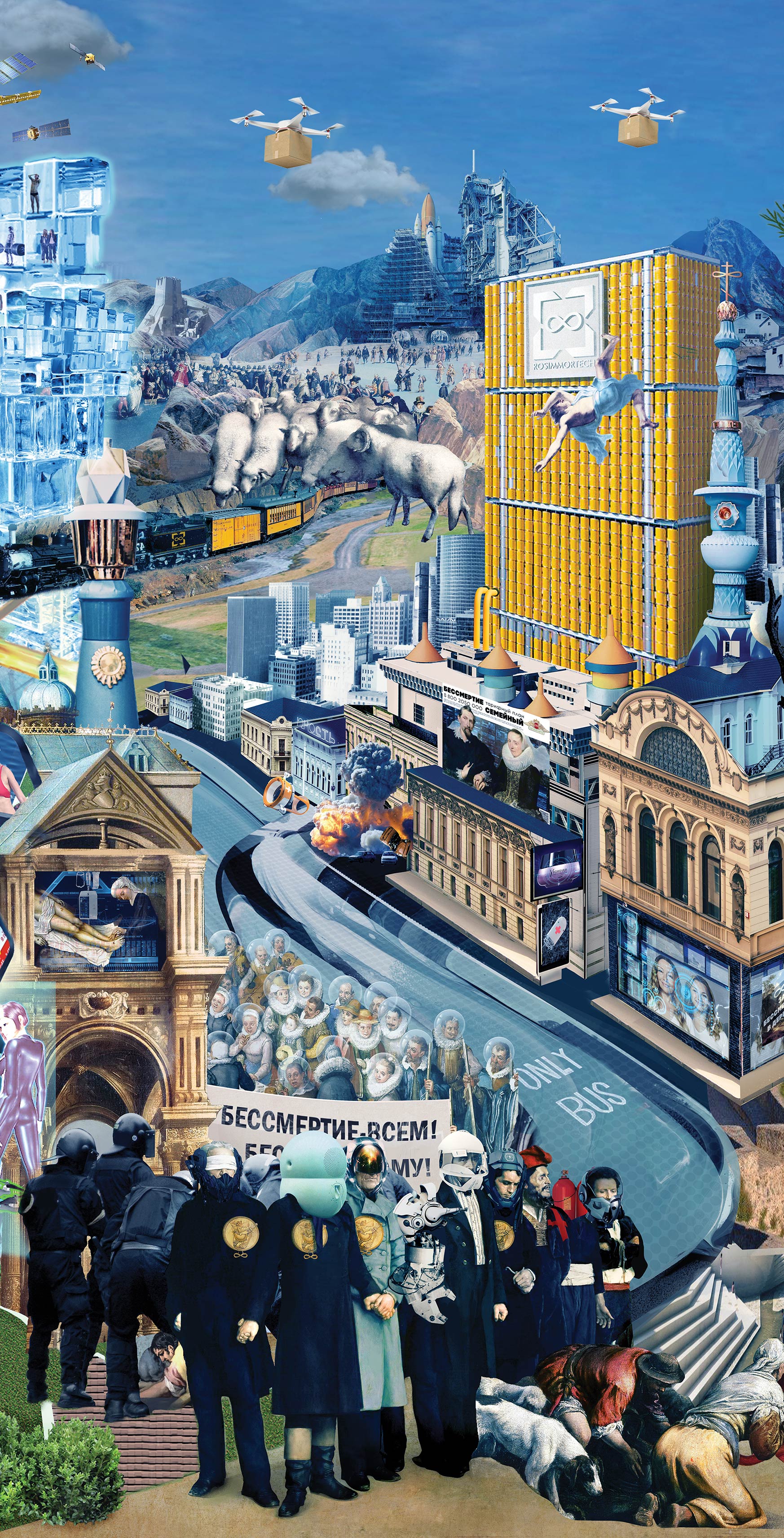

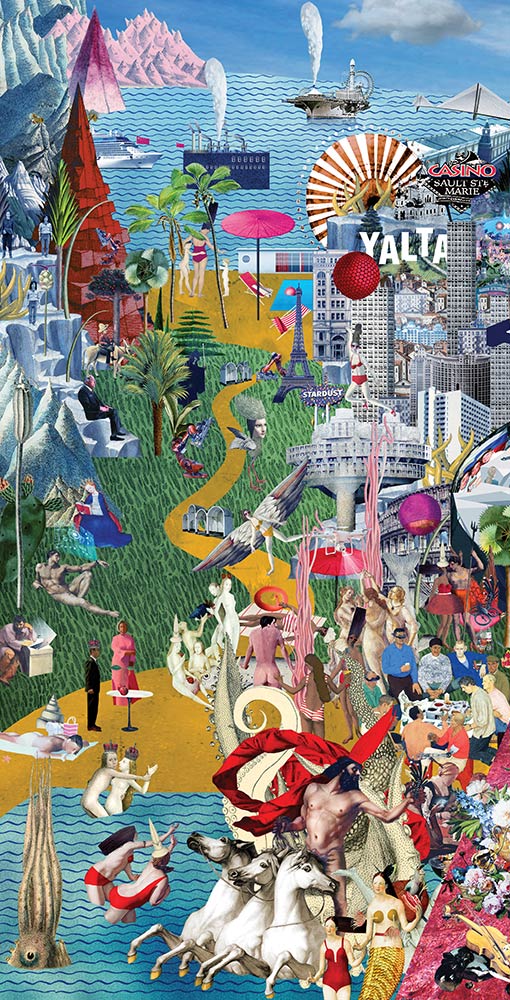

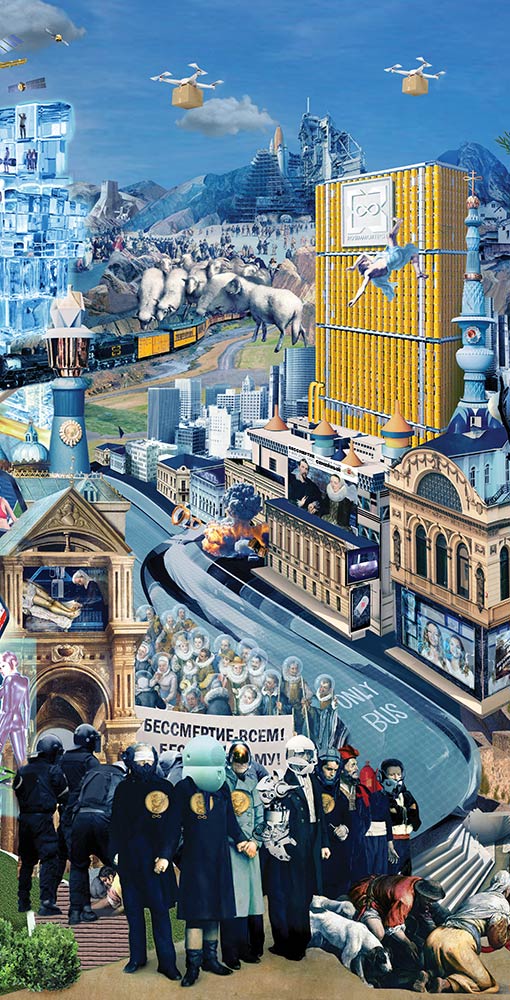

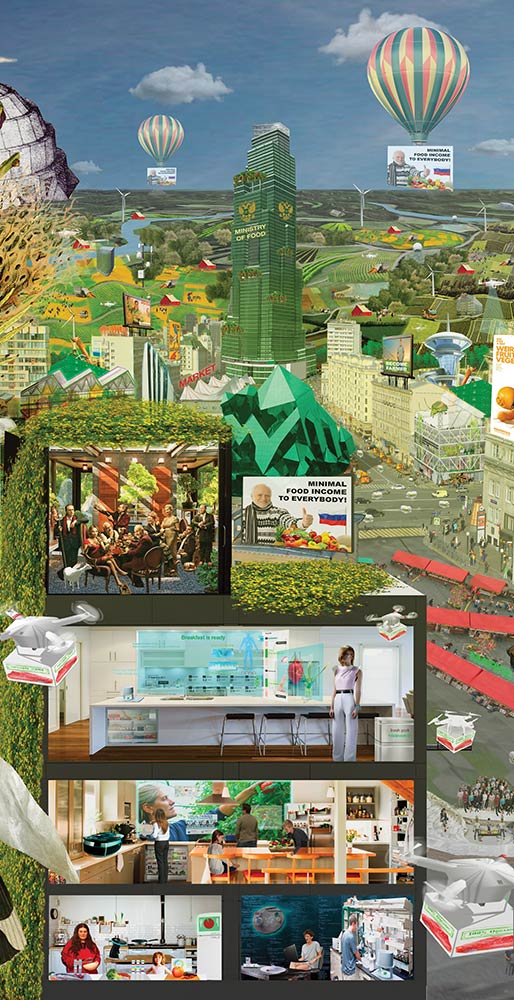

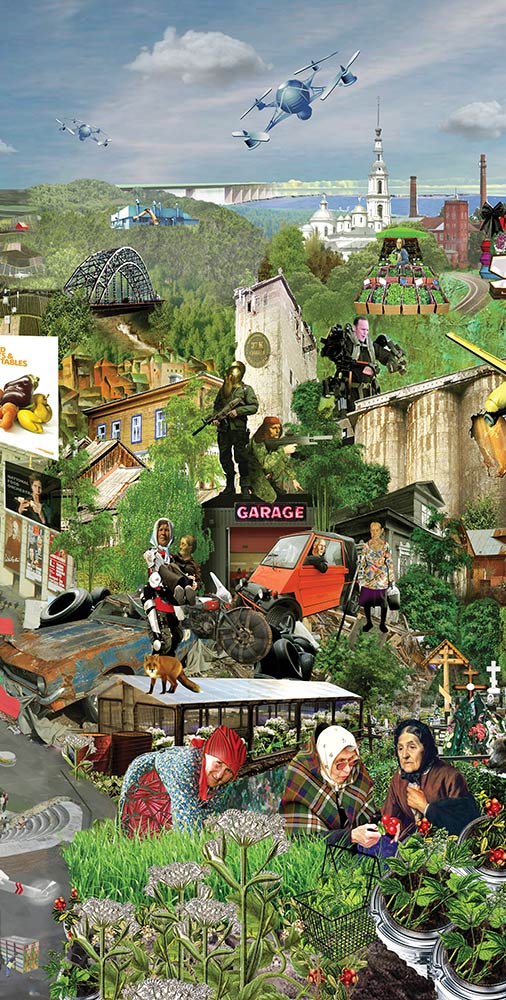

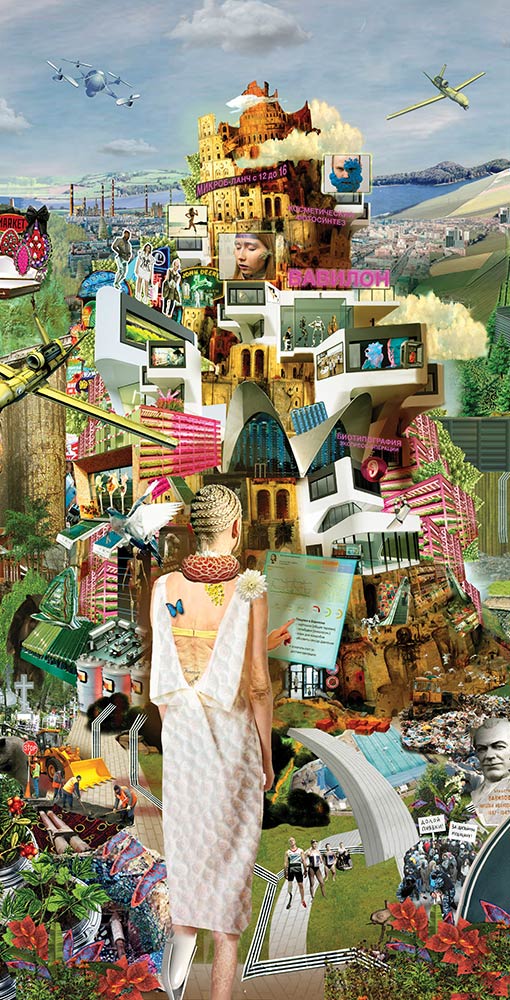

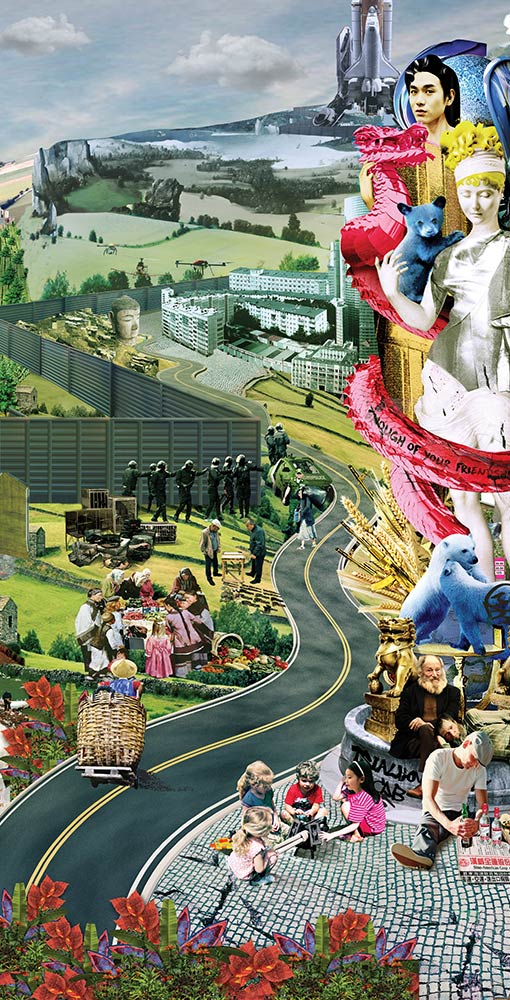

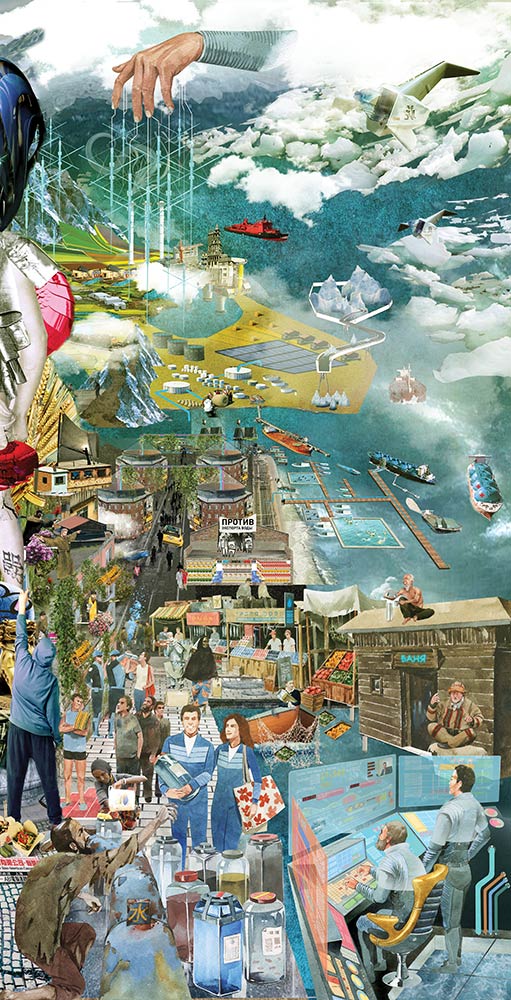

Students of Strelka Institute spent three months exploring global trends that will impact our life in the next century. One of the results of this work is the mural which represents landscape of imaginary Russia in the future. Exhibition of Strelka Institute educational programm

I.

Leisure Economy

I. Leisure Economy

Back to the mural

II.

Alternative Forms of Governance

II. Alternative Forms of Governance

Back to the mural

III.

Heritage Preservation

III. Heritage Preservation

Back to the mural

IV.

Surveillance Society

IV. Surveillance Society

Back to the mural

V.

Immortality

V. Immortality

Back to the mural

VI.

Knowledge Commons

VI. Knowledge Commons

Back to the mural

VII.

Agrarian Evolution

VII. Agrarian Evolution

Back to the mural

VIII.

Shrinking of Industrial Cities

VIII. Shrinking of Industrial Cities

Back to the mural

IX.

Bio-tech City

IX. Bio-tech City

Back to the mural

X.

Chinese Domination

X. Chinese Domination

Back to the mural

XI.

Water Scarcity

XI. Water Scarcity

Back to the mural

|

I

Leisure Economy

|

II

Alternative Forms of Governance

|

III

Heritage Preservation

|

IV

Surveillance Society

|

V

Immortality

|

VI

Knowledge Commons

|

VII

Agrarian Evolution

|

VIII

Shrinking of Industrial Cities

|

IX

Bio-tech City

|

X

Chinese Domination

|

XI

Water Scarcity

|